Category

news, WebAbout This Project

Monday morning I received a text telling me to be careful. Something about bad energy. I made a mental note to ask if another planet was in retrograde for the fifty-eleventh time. But I was quickly snapped out of my levity when I read the next part of the message: My friend informed our group chat that a white man attacked two black women on Bay Area Rapid Transportation (BART) in Oakland, California.

One of them died. The other survived the brutal attack with injuries to her neck. And the assailant was still on the run.

Questions about what happened and the motive behind the attack rushed through my mind as I hurried to get out of the house that morning. (While many suspect the attack to be racially motivated, police have yet to confirm.) And even though I hadn’t completely processed the information, I knew to change my route to work. A route that, every day, finds me standing on the BART platform where Johannes Mehserle took Oscar Grant’s life. Every day I look into a painting of Grant, installed at the station after he was handcuffed and shot by a police officer, staring back at me. A reminder of the black pain in my hometown, the distrust of police, the historical race violence that spurred the creation of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. But the morning I learned about the death of Nia Wilson, an 18-year-old aspiring paramedic and rapper, and the assault on her sister Lahtifa Wilson, I took the bus to San Francisco instead of the train.

Once I got to the office, I pulled up every article I could find to get details. The sisters were attacked at the MacArthur BART station on Sunday night. It was the third reported killing on BART within a week. Local news reported that the incident was random; the sisters hadn’t interacted with the man at all. Police later apprehended a suspect, identified as John Lee Cowell, a 27-year-old man recently released from prison. Cowell also has a history of mental health issues.

There is no doubt that being a woman in this world can be dangerous. In fact, the United Nations Population Fund describes violence against women as “one of the most prevalent human rights violations in the world.”

“It knows no social, economic, or national boundaries,” the website reads. “Worldwide, an estimated one in three women will experience physical or sexual abuse in her lifetime.”

For black women, the stakes are higher. Last year a CDC report found that black women have a homicide rate of 4.4 per 100,000 people, more than any other race of women in this country. The factors vary—from institutional racism, to overpolicing (and underpolicing), intimate-partner violence and more, it’s hard to pinpoint any one reason black women are disproportionately targeted in America. Pair that with the statistics that find black girls are punished more harshly in schools, that we appear to be older than we are, that we’re “fast,” or that we experience less pain than other women (which often ends up deadly for black women seeking medical help or in childbirth), we are left with a narrative that black women and girls don’t need or deserve protection.

Or that anyone will seek justice for us once we’re hurt. Or worse, killed.

Nia Wilson’s brutal killing can’t be examined in a vacuum, siloed from the very real and lived experiences of black women daily. It’s why the outrage has been palpable. Her death is a reminder of the danger we face daily, the stereotypes that perpetuate the ideas that our lives are not to be valued and how far some news outlets will go to maintain that narrative. (One of the local stations decided to post a photo of the victim with what appeared to be a gun. It wasn’t. It was a cell phone case.)

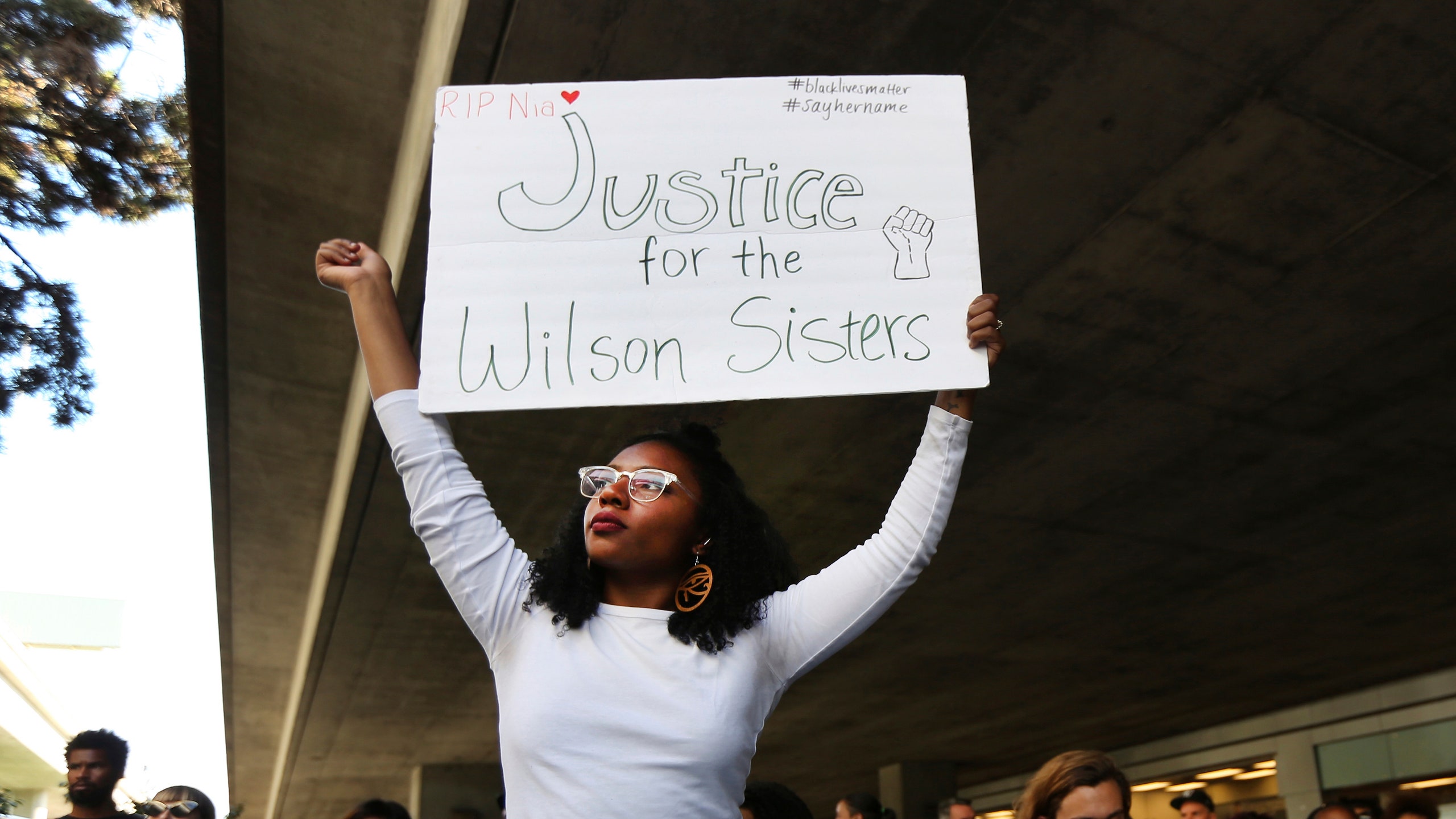

The people of Oakland—many of which are likely daughters and granddaughters born from the civil rights movement and the Black Panther Party—have held demonstrations to bring attention to the crime. This idea, that black women aren’t worthy of being protected, is why women are taking matters into their own hands. It’s why activists like Ashley Yates are crowdsourcing to “place self-defense tools directly into the hands of black women + femmes and queer people in Oakland and the Bay Area.”

It’s why the Anti Police-Terror Project announced that, during a candlelight vigil in Nia Wilson’s honor, Community READY Corps would provide on-site self-defense training for anyone interested.

“We also know that we are each other’s best defense,” the invite read.

I considered the idea of registering for a martial arts class. Maybe it was finally time to go to the shooting range and look into a license. That last thought scared me. And it made me realize how extreme and radical it was, that black women in 2018 must arm themselves to ward off an attack when going through the benign routines of our lives.

Who else faces this degree of terror?

Here are the facts: Black women, cis and trans, are killed at higher rates in the U.S. than women of any other race. #YouOkSis and #SayHerNameserve as constant reminders that black women and girls don’t get justice. Every day we are fighting for basic rights, whether it be equal pay or proper treatment in the classroom. We fight to stay alive during childbirth and to be able to make it home alive from our regular travels.

That’s a level of fight, a level of fear that is deeply unique for us. However, it shouldn’t concern only us.

Nia Wilson’s death is a problem for all of us. In the last week it’s been great to see the number of people coming together, sharing messages about the value of black lives, and refusing to remain silent. But until everyone in the country is truly invested in the lives and safety of black women—beyond posts and hashtags—we’ll never reach full liberation.